Why the World Is Turning to Japanese Calligraphy: The Cultural, Educational, and Mindful Power of Writing by Hand

In an increasingly digital world, the simple act of writing by hand is being rediscovered across the globe.

Japanese calligraphy, known as Shodō, offers a profound practice that enriches education, nurtures the mind, and embodies culture itself.

In this article, we explore its unique appeal and how to begin practicing it — through both Japanese tradition and a global perspective.

In an age dominated by screens and digital input, the quiet, intentional act of writing with a brush has taken on new meaning. Japanese calligraphy, or Shodō (書道), is more than just beautiful characters on paper — it is a practice that fosters focus, creativity, emotional wellness, and cultural understanding.

This article explores why Shodō is gaining international attention, its educational benefits, the mindful experience it offers, and its deep cultural significance — especially as it nears registration as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Why Japanese Calligraphy Now?

Calligraphy in Japan has long been seen as a cultural and spiritual art. But today, its relevance is expanding far beyond its traditional context.

People around the world are beginning to rediscover the joy of handwriting. In contrast to typing on a keyboard, the physical act of writing with a brush engages the body, stimulates the brain, and calms the mind.

Shodō is not just for artists or scholars — it’s a mindful, educational, and culturally immersive experience that anyone can begin.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

The Educational Benefits of Writing by Hand

Studies continue to show that handwriting enhances cognitive development and learning.

According to research from the University of Washington, elementary school children who wrote essays by hand produced more complete sentences and acquired reading skills faster than those who typed.

Why does this happen?

Writing by hand activates multiple areas of the brain simultaneously

It improves information retention and understanding

It builds fine motor skills and attention span

It increases long-term memory recall

Another study found that college students who took handwritten notes performed better on tests and retained the information longer than those who typed their notes.

In essence, handwriting — especially the deliberate strokes of calligraphy — is not just an output, but a learning tool in itself.

Shodō as Mindfulness: A Calm in the Noise

Japanese calligraphy shares many principles with mindfulness and meditation.

The process begins with preparing the ink, grounding yourself, and entering a state of quiet focus. The brush meets the paper. Your breath aligns with your movement. You are fully present.

Practicing calligraphy brings:

A sense of inner calm and mental clarity

A break from the constant noise of notifications and screens

A way to connect with yourself through intentional motion

An appreciation of imperfection and flow

For many, Shodō becomes a form of active meditation — offering peace in motion, silence in expression.

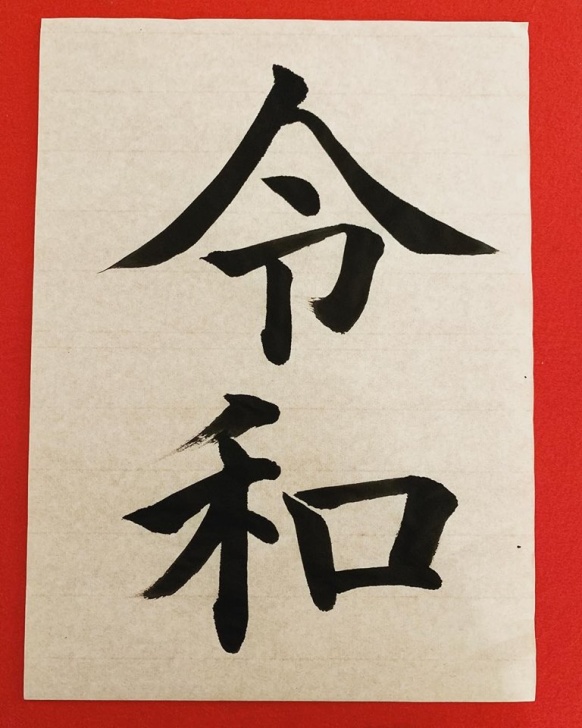

Culture in Every Stroke: The Philosophy of “Dō”

Shodō is more than handwriting. The “dō (道)” in its name means “the way” or “the path,” like in Sadō (茶道 — tea ceremony) or Kadō (華道 — flower arrangement).

Become a member

This implies a lifelong discipline — a spiritual journey rather than a skill to master.

Shodō expresses:

Wabi-sabi: beauty in imperfection

Ma: the meaningful use of space and timing

A respect for tools — brush, ink, paper, and inkstone

A balance between form and feeling

Every stroke is infused with energy. The focus is not only on what is written, but how it is written — with presence, care, and cultural reverence.

Going Global: Shodō and UNESCO

In November 2026, Shodō is expected to be officially inscribed as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

This recognition signifies more than honor — it positions Japanese calligraphy as a shared cultural treasure of humanity.

Interest in Shodō is growing worldwide, with more international workshops, exhibitions, and online courses than ever before.

Students, artists, and seekers from every continent are finding value in the beauty and discipline of brushwork.

Shodō is becoming a bridge — connecting people across borders through shared appreciation of tradition, focus, and creative expression.

How to Begin Your Calligraphy Journey

You don’t have to be fluent in Japanese or a professional artist to begin practicing Shodō.

Here’s how to get started:

Gather basic tools: brush (fude), ink (sumi), paper (washi), inkstone (suzuri)

Set aside quiet time to practice, even just 10 minutes

Start with simple kanji or hiragana characters

Join a local or online class to learn structure and rhythm

Focus on the process, not perfection

Even one stroke can shift your mindset. Each session can become a grounding ritual in your day.

Conclusion: A Global Path to Inner Peace

Japanese calligraphy is not just an art form — it’s a way to educate the mind, heal the heart, and reconnect with culture.

As Shodō gains international recognition, now is the perfect moment to explore its value for yourself.

Whether you’re a student seeking deeper learning, an artist looking for inspiration, or simply someone who wants more presence in daily life — Shodō offers a quiet revolution.

One brush. One stroke. One breath at a time.